A Strange & Beautiful Thing at The Town Hall

It’s a sweet curse when music takes hold of your imagination. The world becomes a kaleidoscope of unresolved longings.

Growing up in Lucknow, India, my life was shaped by a multitude of songs. On Sunday mornings my father played his prodigious collection of vinyl: Chopin and Bach, K. L. Saigal, Begum Akhtar — a chanteuse from my hometown and once a patient of my uncle the doctor — Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, and heavy doses of Qawwali, the trippy Sufi music that drew me in with its hypnotic beats and incantatory rhythms.

Our house echoed with the Sabri Brothers, Aziz Mian, Munshi Raziuddin, Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan. These wild men sang of mad love, surrender, and intoxication. To teenage ears it sounded forbidden, lustful. Only later did I understand these were love songs to God.

Meanwhile, in my Catholic school, another soundtrack pressed against me: Dylan, Led Zeppelin, The Who, Aretha Franklin, Mahalia Jackson, Sam Cooke, Sister Rosetta Tharpe. Music arrived in turbulent waves — shortwave broadcasts, cassettes smuggled back by friends, LPs traded in back alleys.

For many, music became the soundtrack of youth — a place to return, preserved in nostalgic amber. For me, it was oxygen. Petrol. Gabapentin and LSD. A sky on which I painted my career.

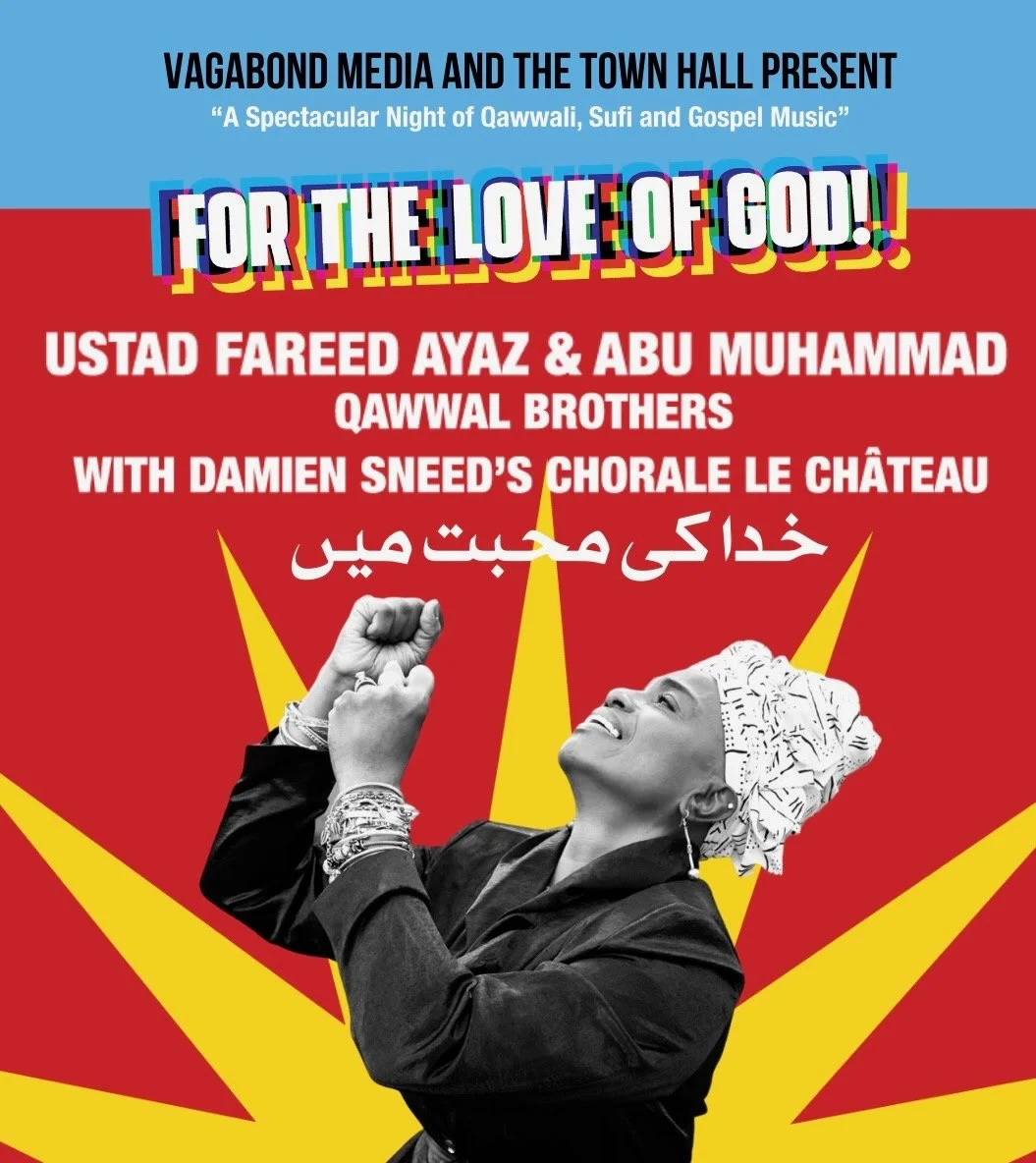

On October 30th, 2025, I will stage a radical experiment in music at New York’s legendary Town Hall, bringing together the two musics of my youth. The concert, For the Love of God!, unites two ecstatic traditions rarely heard in the same breath: the mad devotion of Sufi Qawwali and the soaring power of Gospel.

At its heart are Ustad Fareed Ayaz and Ustad Abu Muhammad Qawwal Brothers — among the last great torchbearers of a 700-year-old lineage reaching back to Amir Khusrau. In dialogue with them will be New York’s finest gospel singers, with the acclaimed Chorale Le Chateau and a powerful orchestra curated by Damien Sneed. Together, they will create a luminous, unlikely rendezvous — a bridge of sound and spirit across cultures and centuries.

The Town Hall is no ordinary stage. It is where Billie Holiday, Nina Simone, Bob Dylan, and Paul Robeson once transformed music into myth. Where suffragists and radicals shook the nation awake. On October 30th, it becomes the site of another experiment in cultural alchemy: Qawwali meets Gospel, devotion meets emancipation, storm and fire, gunpowder and sky.

For two decades at MTV, I produced and curated global pop culture — connecting worlds, amplifying voices, chasing the sound of transformation. For the Love of God! continues that renegade journey, but distilled into something more urgent and sacred: music as rebellion, transcendence, and unity.

A Spectacular Night of Gospel and Sufi Music

at The Town Hall, Oct 30th, 2025

Marcelle Davies-Lashley, Gospel Singer with Chorale Le Chateau

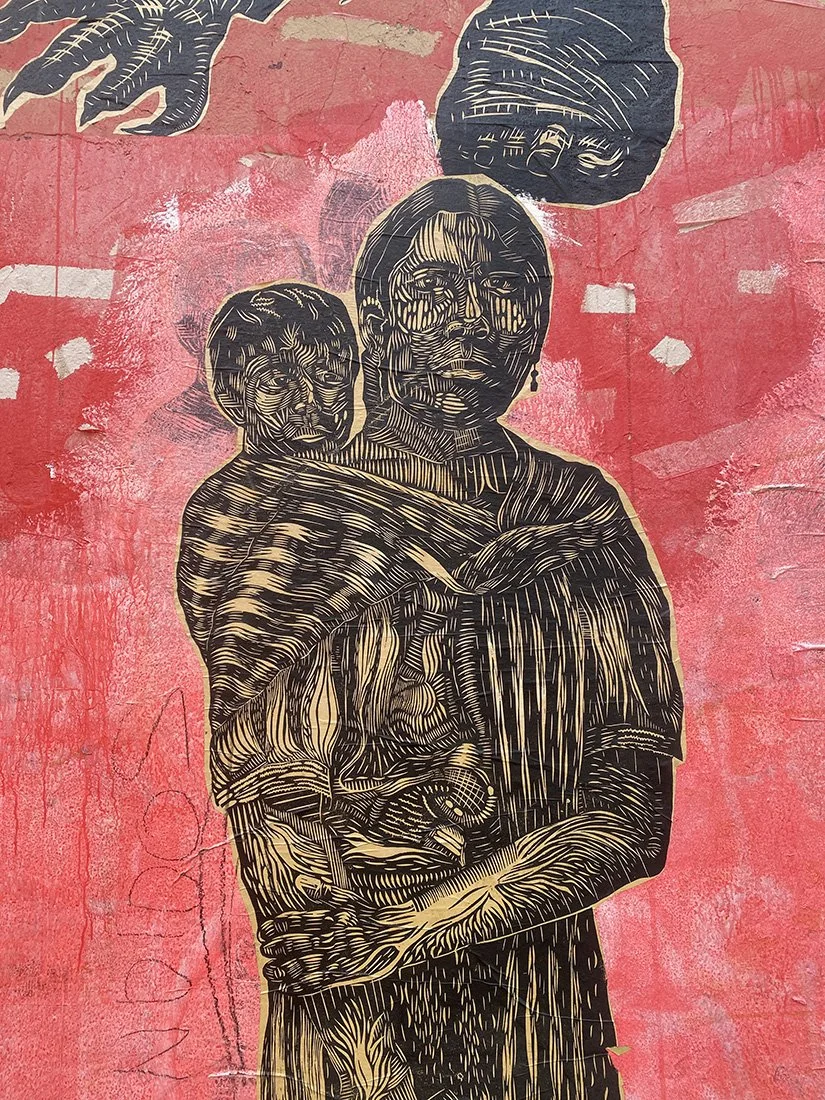

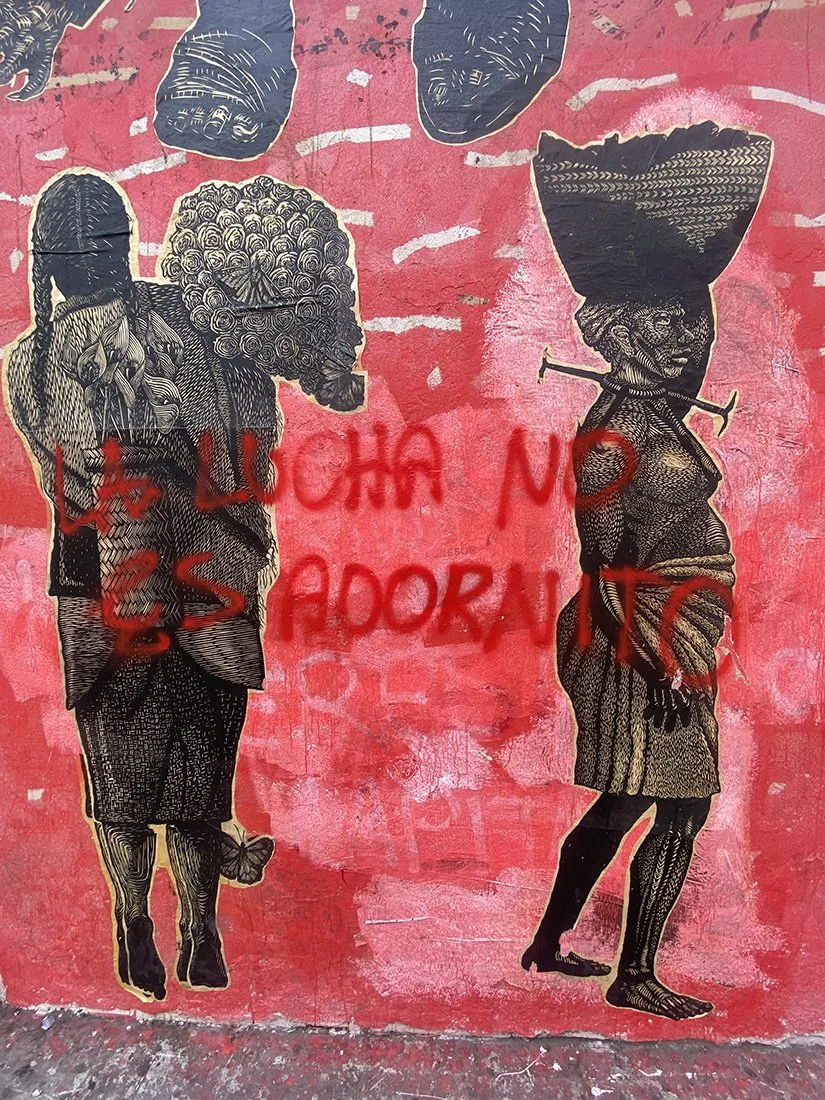

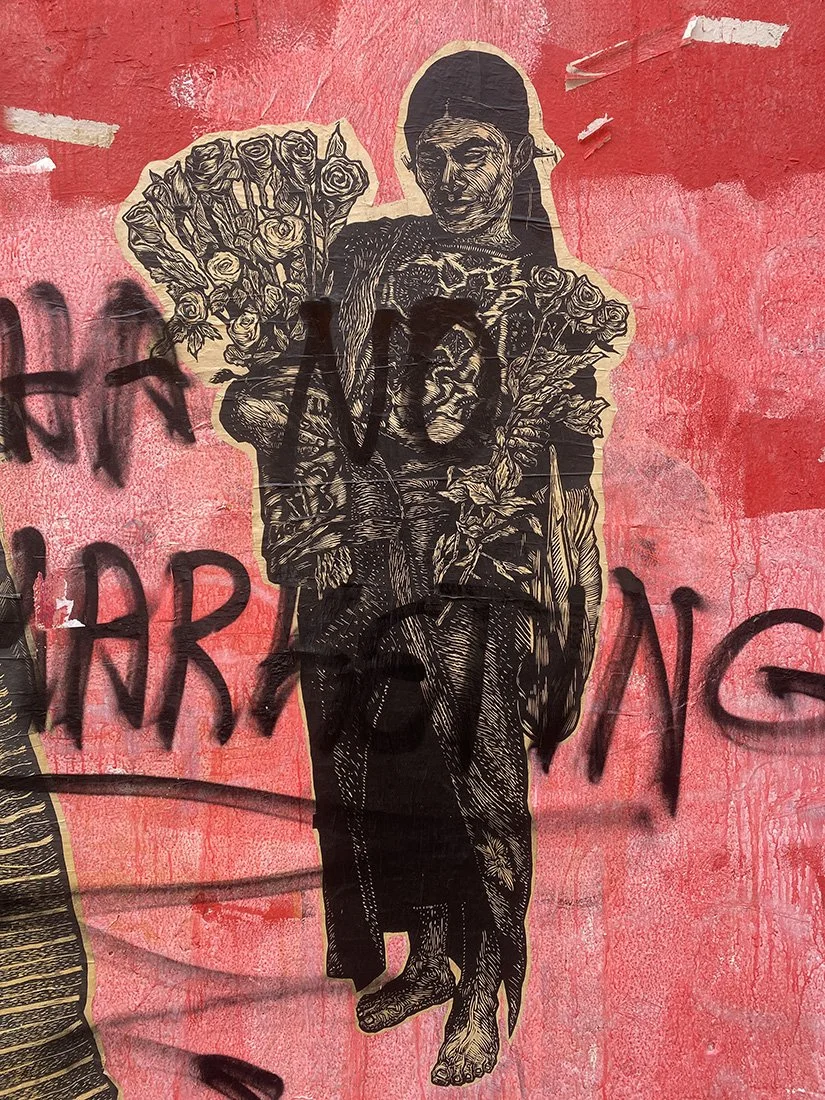

The woodcut art of Oaxaca, Mexico, is raw, urgent, & deeply political. Carved into wood, inked,& pressed onto paper, these prints carry the weight of history in their bold, unflinching, gothic lines. The kind of art missing from the streets of New York or Paris or London and epicenters of the West whose ideals are being ripped apart by hypocrisy, racism and xenophobia.

Inspired by the legacy of José Guadalupe Posada & the resistance movements of Mexico, Oaxacan printmakers use their craft as a form of protest—denouncing injustice, celebrating indigenous identity, & keeping the revolutionary spirit alive. Collectives like Subterráneos, an artist collective composed of young students of different levels and disciplines coordinated by Mario Guzmán and ASARO (Asamblea de Artistas Revolucionarios de Oaxaca) turn the city’s walls into galleries of dissent, where every pasted print is an act of defiance, every carving a refusal to be erased.

Oaxaca’s streets pulse with poetic discontent, its rough walls carved with the faces of resistance. Emiliano Zapata, Benito Juárez, & anonymous campesinos stare out with fierce determination etched in thick, black lines, their expressions unwavering, their presence undeniable. These images aren’t just decoration; they’re calls to action, echoes of past struggles that refuse to fade.

A campesino rides a massive ear of corn like a warhorse, a machete clutched in his weathered hand. He is not just a man but a myth, a guardian of the fields, a symbol of land & labor, of survival itself.

Down de Mariano Abasolom, a woman rises from a storm of gears & flames, her fist raised, her body forged in defiance. She is industry & rebellion, the machine twisted to serve the worker, not the Masters of War. And then there is the warrior on Manuel Garcia Vigil, shrouded in beasts—wolves, antelope, goats—his gaze steady, unflinching. He walks between worlds, carrying history & prophecy in his bones.

This is art made with knives, with fire, with hands that have tilled the soil & clenched in protest. Each print is a wound & a weapon, each stroke a battle cry. Machetes gleam, cornfields hum with resistance, the ghosts of revolutionaries march in ink. Oaxaca does not forget. Its walls speak, shout, demand. This is not just art—it is uprising, it is memory, it is the unrelenting pulse of a city that refuses to be silenced in a world gone wrong.

The Revolutionary Art on the Streets of Oaxaca

El arte de los grabados en madera de Oaxaca es crudo, urgente y profundamente político. Tallados en madera, entintados y prensados en papel, estos grabados llevan el peso de la historia en sus líneas gruesas, inquebrantables y góticas. Un tipo de arte ausente en las calles de Nueva York, París o Londres y en los epicentros de Occidente, cuyos ideales están siendo desgarrados por la hipocresía, el racismo y la xenofobia.

Inspirados en el legado de José Guadalupe Posada y en los movimientos de resistencia de México, los grabadores oaxaqueños usan su oficio como una forma de protesta: denunciando la injusticia, celebrando la identidad indígena y manteniendo vivo el espíritu revolucionario Colectivos como Subterráneos, un colectivo de artistas compuesto por jóvenes estudiantes de diferentes niveles y disciplinas, liderado por Mario Guzmán, y ASARO (Asamblea de Artistas Revolucionarios de Oaxaca), convierten las paredes de la ciudad en galerías de disidencia, donde cada grabado pegado es un acto de desafío, cada talla una negativa a ser borrado.

Las calles de Oaxaca laten con disidencia, sus muros rugosos están tallados con los rostros de la resistencia. Emiliano Zapata, Benito Juárez y campesinos anónimos miran hacia afuera con feroz determinación—grabados en gruesas líneas negras, sus expresiones inquebrantables, su presencia innegable. Estas imágenes no son solo decoración; son llamados a la acción, ecos de luchas pasadas que se niegan a desvanecerse.

Un campesino cabalga un enorme mazorca de maíz como un corcel de guerra, con un machete aferrado en su mano desgastada. No es solo un hombre, sino un mito, un guardián de los campos, un símbolo de la tierra y el trabajo, de la supervivencia misma. En la calle Mariano Abasolom, una mujer se levanta de una tormenta de engranajes y llamas, su puño levantado, su cuerpo forjado en desafío. Ella es industria y rebelión, la máquina torcida para servir al trabajador, no a los Maestros de la Guerra. Y luego está el guerrero en Manuel García Vigil, envuelto en bestias lobos, antílopes, cabras—su mirada firme, inquebrantable. Camina entre mundos, llevando la historia y la profecía en sus huesos.

Este es un arte hecho con cuchillos, con fuego, con manos que han labrado la tierra y se han cerrado en protesta. Cada grabado es una herida y un arma, cada trazo un grito de batalla. Los machetes brillan, los campos de maíz cantan con resistencia, los fantasmas de los revolucionarios marchan en tinta. Oaxaca no olvida. Sus muros hablan, gritan, exigen. Esto no es solo arte—es un levantamiento, es memoria, es el latido imparable de una ciudad que se niega a ser silenciada en un mundo que ha salido mal.

El Arte Revolucionario en las Calles de Oaxaca

A Memory of Namibia

In Namibia, I drove you through relics of long-dried lakes:

Extinct beasts rose from orange dust—

Rhinos pursued by wild dogs, elephants lurching in shambles.

The savannah shimmered silver & gold as your finger accused the Skeleton Coast,

Where we were shipwrecked, surviving on whale flesh,

Held aloft by seal bones & fishermen’s tears.

Let’s tally the lost as springbok vault across the burning sky:

2,200 black rhinos, 3,500 cheetahs, 20,007 elephants, 703 lions,

8,859 zebras, 18,034 wildebeest, 12,008 Angolan giraffes, 373,204 oryx—

A river of Nama children’s tears for 10,000 slaughtered parents,

Drowned in German cruelty, piss & beer steeped in the soil.

medical horrors, rape, barbarism—efficient, unrepentant, deadly.

Did you count the 68,802 Herero dead:

Strung from trees, poisoned in wells, shot, starved, devoured by dogs,

Executed in dreams, erased in the night.

A homosexual Kaiser, white supremacists, Teutonic fascists

Rehearsing for grander genocides—

But for this erasure of black bodies, a few billion euros, a hollow regret,

More piss, beer & sauerkraut in Swakopmund.

Now I take you, my love, to the lighthouse,

Pointing across the Atlantic, where the enemy sailed in 1892,

Ferocious with bottled white curses they shattered on our shores—

To make a ghost widow of you, a ghost orphan of me.